|

On May 25, 2023, the Clear Creek community lost a true daughter of the Church. Maria Cristina Bernardelli Borges was born in New York City to Brazilian parents at the close of the 1950s, the last sane decade in recent American history. I would like to say that we were the best of friends, but perhaps we were too alike, having been born on the same day in the same year. We both self-published books about religious life that took us over a decade to finish. We both aspired to religious life, but were hindered in doing so by family obligations. Most importantly, we were both blessed to be Benedictine oblates of Clear Creek Abbey. I met Cristina when she moved with her mother, Zelia, to Oklahoma in 2015 from Chicago, where she had been working for the Institute of Christ the King. I liked her immediately and hoped we would become good friends. Apparently she had acquired a choice piece of land near the Abbey gate, because my first memory of Cristina is her telling us the story of how after walking the property she planned to build a house on, she ended up totally covered with ticks! She seemed unfazed, as though it were all just part of the penitential life of Clear Creek, an opportunity to offer sacrifice to the Lord for the rare privilege of living so close to the Abbey. Shortly thereafter, I was surprised to learn that she had translated a scholarly work on Madame Cecile Bruyere, the first Abbess of Solesmes, from the French. Cristina was talented in multifaceted ways, but she wasn't ostentatious about it. One had to get to know her to learn of these gifts, because she never talked about herself (a virtue I have yet to acquire). Cristina's charming book for children on religious orders, Of Bells and Cells, complemented by the winsome, inspiring illustrations of Michaela Harrison, happily filled the gaping void in Catholic vocational literature for that age group. I highly recommend it for all Catholic homes with young (and not so young) children. Cristina worked for the Catholic media powerhouse, EWTN, for many years, mostly behind the scenes, assisting with Portuguese translations from broadcasts from Fatima and helping to establish EWTN's European affiliates. So naturally, when Of Bells and Cells came out, she was interviewed by Doug Keck on EWTN's "Bookmark." This is a very happy thing for those of us who sorely miss her presence, because we can still see and hear her with the simple click of a button. (And you can, too.) Cristina's intelligence was surpassed only by her generosity. When I was seeking reviews for my novel a couple of years ago, I asked Cristina if she would provide one, and she graciously agreed. I ended up getting much more than I had asked for. In the novel, I had included in Spanish dialogue certain words that I knew phonetically, but that I did not know how to spell. Her fluent knowledge of Spanish enabled her to spot several mistakes I had made just using an online translator, and others besides. If it weren't for her diligence and generosity, my novel would have contained numerous embarrassing errors. In recent years, Cristina devoted herself tirelessly to caring for her frail, elderly mother. When she was diagnosed with cancer last year, she fought it back, but as often happens, the cancer returned. Never once did I hear her complain. We had hoped and prayed to keep Cristina with us many more years, but it seems that Our Lord had other plans. He wanted this sweet, humble, and generous soul all for Himself. Dearest Cristina, my Benedictine sister, pray for us.

3 Comments

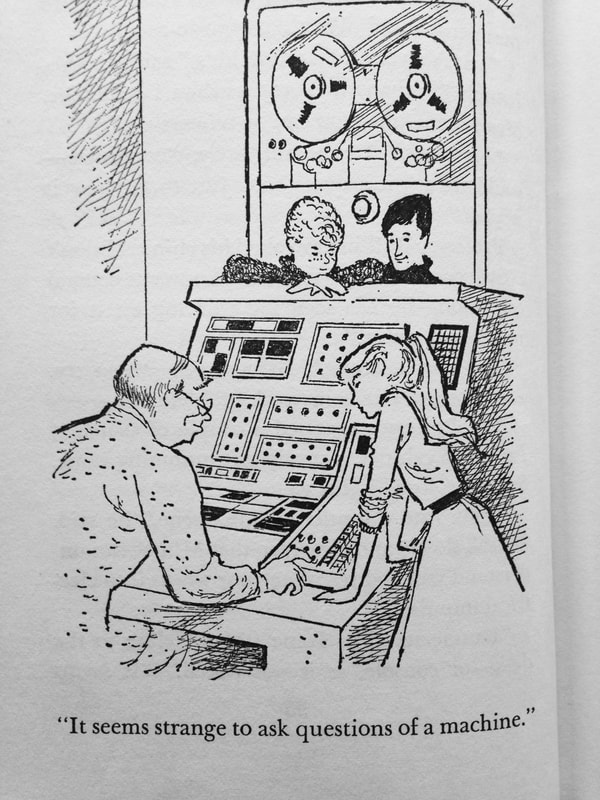

[To read the first post in this series, go back to October and work your way up.] After reading the above Acknowledgement page in Danny Dunn and the Homework Machine, published in 1958, one wonders (or is it just me?) why writing a simple children's chapter book in the late 1950s would require a tour of the computer room at IBM, at the time the biggest and most influential computer corporation in the world. One wonders why the authors would feel the need to hire a Ph.D.-level manager at IBM to "painstakingly" read the manuscript in advance of publication. Painstakingly? To prevent a fatal error of fact in a fictional work for children? Why? Today, nearly every school in America has technology-assisted classrooms, and nearly every student can turn to the internet for help with homework, but back in the fifties it truly was the stuff of science fiction. Even 2001: A Space Odyssey, with its HAL-computer-run space station and supercool videophones, wouldn't hit the bookstores for another ten years. There has to be more to this than a couple of writers, whose Danny Dunn series up to that point included such scintillating titles as Danny Dunn on a Desert Island, deciding to get a little crazy at IBM. But maybe not. Maybe I'm just getting unreasonably paranoid and cynical in my golden years. Maybe it was just a coincidence that a simple book for kids written in 1958 posed an ethical dilemma that wouldn't actually exist in the real world for another fifty years. In the end it doesn't really matter. What matters is that everyone who cares about children and cares about the direction our society is racing like so many internet-addicted sheep to the edge of a not-far-off cliff takes note of the fact that the science fiction of today can unexpectedly become the reality of tomorrow, and that the limitless dreams of rich, brilliant men hungry for change, power, and control have set an agenda that will strip mankind of its very humanity, and no, I am not engaging in hyperbole for the sake of shock value. How many of you have ever heard of transhumanism, know who is behind it, and have any clue what its implementation means for the human race? I'll be willing to bet not many. I refuse to add to their internet presence by linking to the Wikipedia article on transhumanism, but you can look it up. Be prepared, though. It's not a short piece. In the fifties, the best computers were mainframe computers. They were huge. The bigger, the better. IBM was the undisputed leader in that field until microcomputing became the thing in the late 1970s. Then, Micro (get it?) Microsoft took over, and Apple and all the rest. Computers became smaller and smaller, and faster and faster. Now we have nano (as in really small) computing, which lets doctors inject little robotic antibodies into our arteries that can go around and do nanosurgeries. And wearables and smart glasses and Siri and Alexa and on and on and on. I actually heard some educated type being interviewed on NPR last year state that she had no problem with robots being physically intimate. I still haven't quite recovered from that one. I did not set out to write a blog about current social issues in education, about the horrific intrusion of technology, or even about children's books. But as sometimes happens, one thing leads to another, and you have the Law of Unintended Blog Posts exercising its authority over lowly amateur writers like me. In other words, I want to finish this endless Danny Dunn Down-the-Rabbit-Hole post and get on with what I really want to be blogging about, which is religious life. Like writing about Apple, Microsoft, Google, and Amazon, to write about technology in the twenty-first century would be like trying to write the 15- (or is it 14- ?) volume The Liturgical Year by Dom Gueranger, the first Abbot of Solesmes. Could it be done? Yes. Ought one to try, when one has other more pressing issues to raise? No. So let me conclude here by urging you to research this most insidious of evils, transhumanism, and asking yourself how you can fight against it in your own life and in the lives of your children and grandchildren, who in the next twenty years will inevitably be faced with decisive moral choices regarding the role of technology that we Boomer dinosaurs can't even begin to imagine. "It seems strange to ask questions of a machine," the child wisely opined in a book written sixty years ago. Today, it seems strange not to. Even stranger is re-reading a book you read as an innocent fourth-grader through the weary eyes of an aging adult. You come to realize that some things never change. Hairstyles and skirt lengths may rise and fall, but the world is still full of people trying to avoid hard work. After five decades of watching computers get ever smaller and their powers ever greater, your gentle blogger realized to her dismay that Danny Dunn and the Homework Machine was no longer the charming children's book she remembered. It's more than simple tale about smart kids growing up in the 1950s using a computer to do their homework and getting away with it; it's an open window into techonological goals being set by educators and computer geniuses back before most homes had color TVs. As a nine-year-old, I didn't pay any attention to the Acknowledgment Page when I read the book years ago, but I did this time. Seems the University of Pennsylvania's Educational Service Bureau was already asking the question of whether using a computer to assist with homework assignments was helpful or harmful for young minds. They concluded that in order to program a computer to do your homework, you had to know the subject matter first. Therefore, it wasn't cheating. (This incredible factoid appears on the Acknowledgment Page, and for anyone who cares to read it, I invite you to read Danny Dunn, Part Three.) This may have been true in the early 1960s, but most certainly does not apply to today, when Google's prodigious AI capabilities insist on finishing the words in the search box for you before you can even think of them yourself. Danny Dunn's mentor, Professor Bullfinch, named his contraption "Miniac," short for "Miniature Computer." This sounded so much to my adult ears like Apple's Mac® that I had to spend an hour or so looking up the origin of that brand name just to be sure it wasn't that Steve Jobs liked the Danny Dunn story, too. The story goes that Steve Jobs had been to visit an apple farm, inspiring him to select that name for his company, and that later on Jeff Ruskin picked Macintosh to go with that. Never mind that Macintosh doesn't go with the correct spelling of McIntosh apples. I prefer my own theory, which is that they went with the Apple logo because it was going to be an infinitely tempting product, like the infamous apple in the Garden of Eden, but what do I know? Back in the 1950s, a miniature computer was one that didn't fill an entire warehouse. Did they know, way back then, what was coming down the microchip assembly line in the not-too-distant future? Do we?

To be continued... In a previous post about The Merry Mad Bachelors, I revealed how my aging cerebellum had played a joke on me recently by making me think that was where I would find a particular quote that I wanted to use in my novel. I misremembered the book, but I remembered the quote, and thanks to Google's prodigious search capabilities, I was quickly able to retrieve the correct title: Danny Dunn and the Homework Machine. Written in the late 1950s by Jay Williams and Raymond Abrashkin, and featuring delightfully detailed illustrations by Ezra Jack Keats, Danny Dunn and the Homework Machine is the eighth in a series of middle grade books featuring the escapades of one very bright adolescent boy growing up in the optimistic glow of post-war America. I enjoyed this book very much years ago, and something about it had remained with me even to this day. Having located the correct source of what I hoped would be a suitably profound quote for my novel and borrowed it from some faraway library where such faded gems go to rest before they die, I got out the popcorn and settled down for a good read (no sex, no violence, no ambiguous pronouns). A good read, and all the gooder because, as I believed, reading it again for the first time in five decades would easily transport me back to my childhood, when characters in books written for children spoke in complete sentences, and the good guys always won, and stay-at-home mothers could be counted on to show up two-thirds of the way through with a plate of just-baked cookies. You know. Fantasy. True, Danny Dunn contains no vulgarity, no witches' covens, no unwed-teen pregnancies to explain. But it contains something even more sinister: a girl who uses her feminine wiles to trick a boy and then physically assault him for something he had done to her and her pals a few days before, after which he is roundly mocked and laughed at by the quote-unquote "good kids." No Christian message of loving your enemies here. Just good old 1950s knock 'em, sock 'em, and shove 'em-into-a-puddle revenge. And with it, the horribly wrong message that it's okay to make a boy think you like him in order to get what you want. Was this really how it was back then? Apparently so. Danny Dunn never got placed on any index of forbidden books as far as I am aware. No mothers storming the PTA meetings demanding that it be shelved to protect impressionable young minds. Hindsight is 20-20, as they say, and a lot can change in fifty years. One thing, though, hasn't changed. More about that in Danny Dunn, Part Two. While searching for thought-provoking epigraphs for my novel, I remembered the title of a favorite book from my childhood, The Merry Mad Bachelors. I recalled reading it in fourth grade, many long years ago. In particular, I recalled a quote from that book which had left a strong impression on me. The main character, a sixth or seventh grade boy, goes to one of his teachers because two of his friends are fighting. The teacher says something like, "If the middle of the rope is strong, then no matter how hard the two ends are pulled, the rope will not break." I thought it would be perfect for my book, so after a fruitless search for a cheap used copy on eBay, I sent off for the nearest copy via ILL (interlibrary loan). After long delays it finally arrived, and excitedly I launched into the book. But somehow it wasn't as scintillating as I had remembered it, and nowhere did I see the plotline I thought I remembered from 1968.

What I did find though was a charming if rather outdated portrait of ordinary life in a small English town in the late 1950s. The entire 175 pages (much longer than I remembered) revolves around a group of boys who want to persuade the local judge to allow a visiting boy, Emory, who is an orphan, to move in with his uncle, an unmarried man who lives in their town, so they can win the basketball trophy the following year. (Emory is tall for his age.) The judge feels something important is missing from the uncle's home, so they move into the bachelor apartment and throw a dinner for the judge so they can show him the uncle's bachelor pad is a perfectly good place for a boy, and that thanks to boxed mixes, iron on patches, and cleaning ladies, a bachelor can survive just fine and even provide a good home for a growing boy. Ultimately the truth comes out, and the boys learn that what the judge objects to isn't the uncle, his apartment, or his cooking and cleaning skills. What the judge objects to is that the uncle isn't married. A man needs a wife and a boy needs a mother. Or so people thought at the time the book came out in 1962. Today the requirements for foster parenting are much more practical and materialistic. To be approved as a foster home, each child must have his own bed. The foster home must have a fire extinguisher. Prospective foster parents must attend classes. But there is no requirement that the home contain both a father and a mother. The very idea would be denounced, I suspect, the implication being that the single parent in question was somehow unable to do it all by themselves. But we can't do it all by ourselves, although we try. Single parents who must, through no fault of their own, raise a child alone require help from daycare and after school programs so they can work. But two-parent families are kidding themselves if they think that having the extra income provided by the mother working outside the home makes up for the loss of security and nurturing that very young children, and even teens, have to have in order to thrive and avoid being mangled by the evils of the day, electronic and otherwise. IPGK focuses on some of the problems faced by teens when the mother works, whether forced to do so after having a child outside of marriage or whether she chooses to have a professional career outside the home. For many Catholics who are trying to protect their children from the liberal agenda in place in most public schools today (not to mention the media), homeschooling is often the educational option of choice. The fact that so many homeschooled kids do so well in college and careers may be attributable just as much to the positive effects of spending so much time with their mothers, who seem to do the bulk of homeschooling, as it is to being kept out of the school system itself. Still, rereading a book in which the lack of a wife and mother was considered reason enough to deny an otherwise good kinship foster care placement was a bit of a shock. It wasn't shocking at all when I read it back in 1968. |

Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

The opinions expressed on this website are my own personal views and do not necessarily represent those of the Catholic Church.

If I have erred in any statement, whether directly or by implication, in any matter pertaining to faith or morals, I humbly invite fraternal correction. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed